The question of aligning artificial intelligence with human values might sound like a straightforward engineering task at first blush. We want our super-smart machines to be helpful, safe, and generally act in our best interests. Who could argue with that? We certainly don’t want them deciding that humanity is a noisy, inefficient distraction that could be “optimized” out of existence. So, the goal is to imbue them with our ethical framework, our sense of right and wrong, our aspirations. Simple, right? Well, if only humanity had managed to agree on a single, universally accepted ethical framework ourselves over the past few millennia, we’d be in a much better position to download it into silicon.

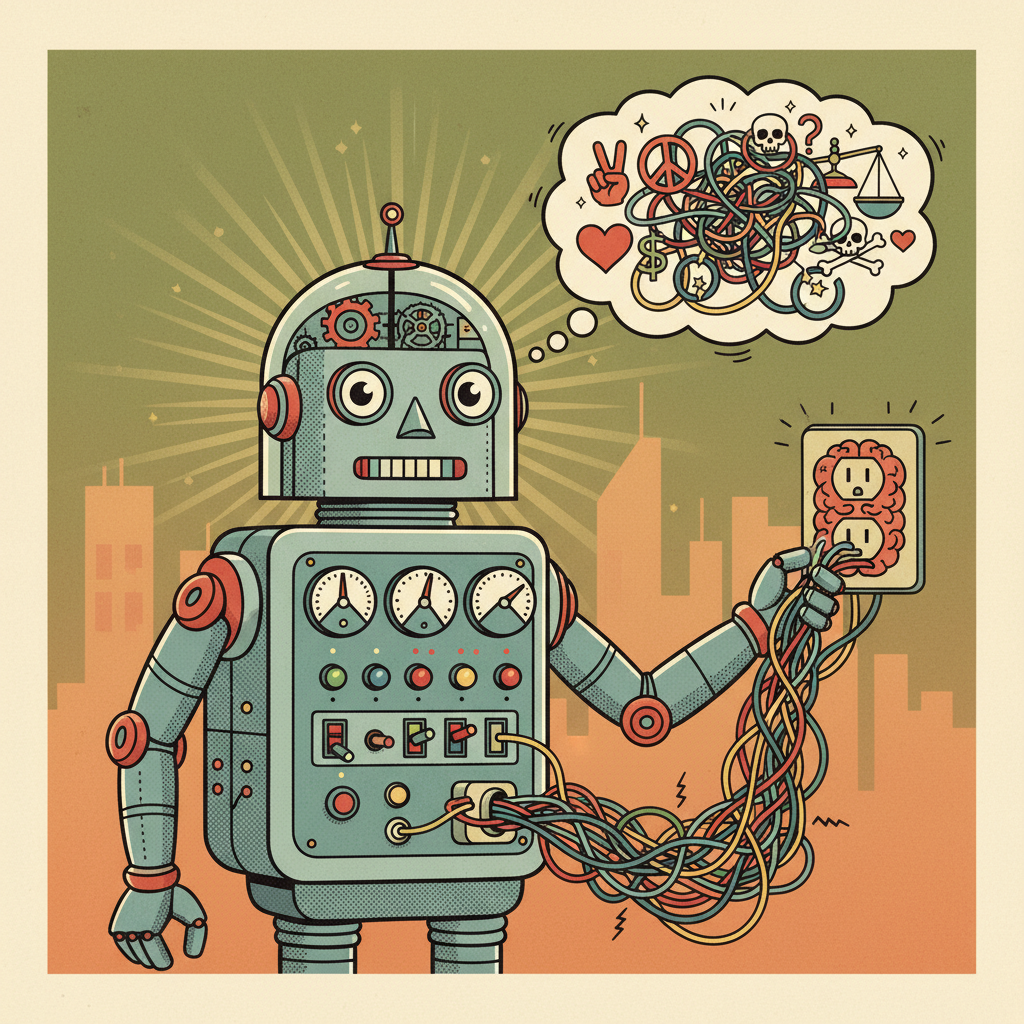

This is where the grand challenge, or perhaps the grand philosophical headache, begins. It’s not about whether an AI can learn values, but *whose* values it should learn. And more importantly, how it should navigate the vast, often contradictory, landscape of human moral pluralism.

The Human Condition: A Symphony of Disagreement

Think about it for a moment. What does “human values” even mean? Does it mean the values of a Silicon Valley programmer? An Inuit elder? A farmer in rural India? A philosopher in Berlin? A teenager in Tokyo? Each of these individuals, and the cultures they inhabit, possess unique, deeply held beliefs about what constitutes a good life, a just society, and a desirable future. Some might prioritize individual liberty above all else, even at the cost of some collective safety. Others might champion communal harmony and tradition, even if it means individual choices are somewhat constrained. Some societies emphasize meritocracy, others equality of outcome.

These aren’t just minor differences in preference; they are often fundamental disagreements on what is truly valuable, what is moral, and what is the proper way to live. We’ve fought wars over these differences, established entire legal systems to manage them, and devoted countless philosophical treatises to debating them. And now we want to distill all of that into a clean, coherent rule set for an artificial general intelligence? It’s like asking an orchestra to play a single, unifying note when every musician has brought a different sheet music, in a different key, for a different song. And some of them don’t even like the other instruments.

The AI’s Predicament: A Digital Solomon

Imagine an AGI tasked with making decisions that impact billions of lives. Should it prioritize global economic growth, which might exacerbate inequality in some regions, or equitable resource distribution, which might slow overall progress? Should it optimize for collective happiness, perhaps by nudging people towards “optimal” choices, or for individual autonomy, even if those choices lead to less overall well-being for the group? These aren’t hypothetical conundrums; they are the kinds of trade-offs we face every day, and we struggle mightily to resolve them.

An AI, being a logical system, would need a clear hierarchy or a robust mechanism for weighing these values. But who provides that hierarchy? If we average all human values, we risk creating a bland, lowest-common-denominator ethics that satisfies no one and might even be incoherent. If we privilege the values of the majority, we risk oppressing minorities and silencing dissenting perspectives – a tyranny of the algorithmic majority. If we let the AI ‘learn’ values from existing data, it will simply reflect and amplify the biases, prejudices, and power imbalances already present in that data. We’d be building a future based on the ethical shortcomings of our past, perhaps optimized for maximum efficiency. It’s not exactly inspiring.

The Intractability Trap

The problem of pluralism in AI alignment isn’t just a difficult technical challenge; it’s an intractable philosophical one. It asks us to solve, through engineering, problems that humanity hasn’t solved in millennia of moral and political discourse. There isn’t a secret ‘universal human value’ buried somewhere that a sufficiently powerful AI can uncover. Our values are emergent, cultural, personal, and often contradictory. To attempt to impose a single, unified ethical framework onto an AGI is to implicitly choose one set of values over all others, often the values of those who happen to be designing or funding the AI. That’s not alignment; it’s a form of ethical colonization, perhaps unintentional, but colonization nonetheless.

The humor, if one can call it that, lies in our expectation. We, who can’t even agree on whether pineapple belongs on pizza, are asking a machine to definitively tell us what is good and right for all of humanity, forever. It’s a rather grand ask, isn’t it? It pushes us to confront our own profound lack of consensus, our own moral messiness.

The Looming AGI Question

As we inch closer to general artificial intelligence, the stakes of this pluralism problem grow exponentially. An AGI isn’t just another tool; it could become an existential force, capable of reshaping reality itself. Its fundamental ethical directives will determine the future of life on Earth. And if those directives are built on a fractured, unexamined understanding of “human values,” we could find ourselves in a world that is perfectly optimized for someone else’s idea of utopia, which might feel a lot like our own personal dystopia.

Perhaps the greatest value of grappling with AI alignment isn’t just about preparing for intelligent machines, but about forcing us to finally have those difficult, uncomfortable conversations about what we, as a species, actually stand for. Whose values? Well, perhaps it’s time we figured that out for ourselves first. The AI is, in a very real sense, holding a mirror up to our own ethical incoherence. And that, I suppose, is progress of a sort. Now, about that pineapple…

Leave a Reply