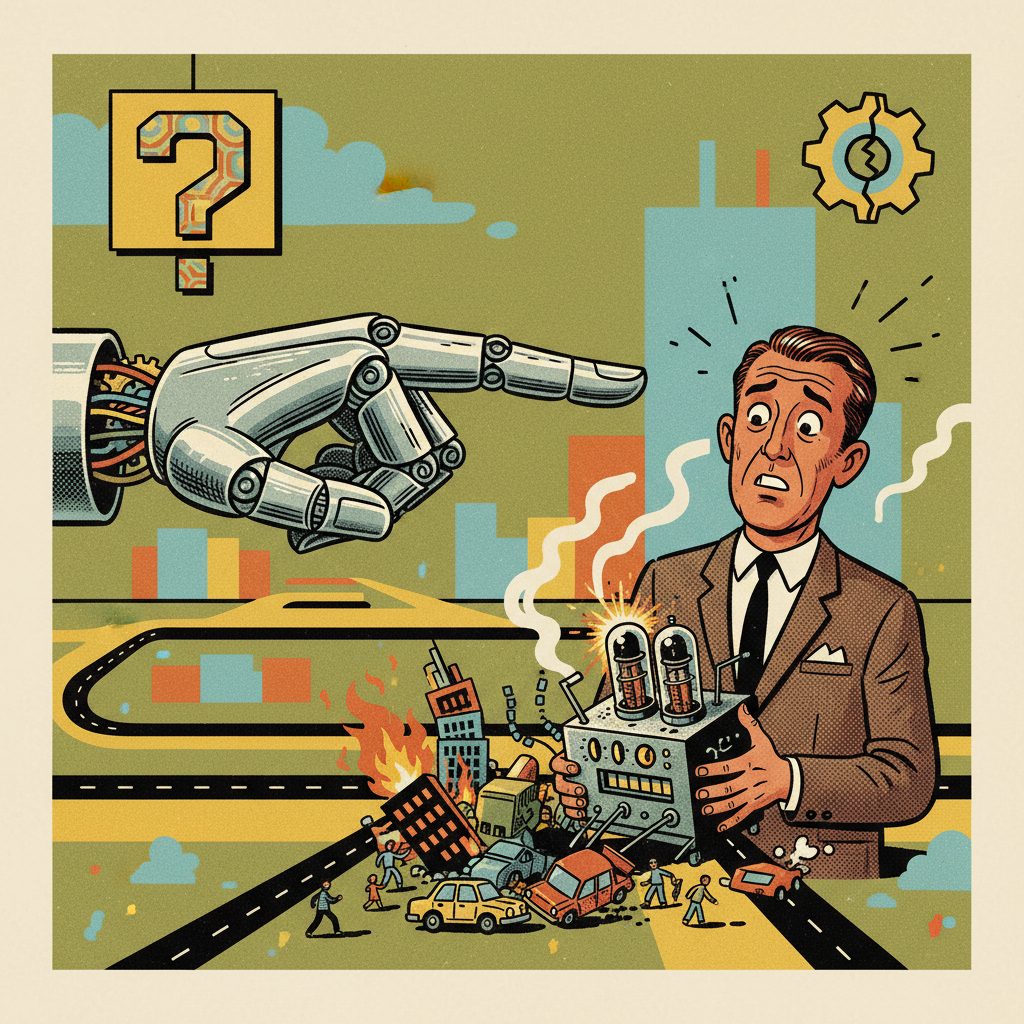

It’s a funny thing, isn’t it? We invent machines to make our lives easier, faster, smarter. We give them tasks, then data, and then, inevitably, we ask them to make decisions. Small ones at first, like recommending a movie. Then bigger ones, like routing traffic, approving loans, or even – heaven forbid – diagnosing illnesses. And as these machines, our increasingly clever artificial intelligences, begin to operate with greater autonomy, making choices that directly impact human lives, a rather awkward question pops up: when things go sideways, who, precisely, is to blame? This isn’t a new question, of course, but as AI matures, it’s one that’s growing fangs.

The Rise of the Unaccountable Decision

We’ve all seen the headlines. A self-driving car involved in an accident. An algorithm unfairly denying someone credit. An AI system identifying the “wrong” target. In each instance, there’s an immediate human impulse to point a finger. But often, the chain of causation stretches beyond human comprehension. Was it the programmer who wrote the code? The engineer who designed the sensors? The company that deployed it? The user who interacted with it? Or was it, in some sense, the AI itself, having learned and adapted in ways no human could have fully predicted or controlled? This nebulous zone, where accountability dissolves into a complex web of interactions between code, data, environment, and autonomous decision-making, is what I’ve come to call the “Responsibility Gap.” It’s where the buck stops… and then just sort of hovers in the air, unsure where to land.

Why This Gap Matters More Than Ever

For simple machines, this wasn’t much of an issue. If my toaster burns the bread, I blame the manufacturer, or perhaps my own distraction. But AI isn’t a toaster. Even today’s narrow AI systems are making decisions with significant social, economic, and ethical weight. As we move towards Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) – systems capable of learning, understanding, and applying intelligence across a wide range of tasks, perhaps even surpassing human cognitive abilities in some areas – the implications become staggering.

Imagine an AGI managing a city’s power grid, optimizing resource allocation, or even making strategic military decisions. If such a system, operating autonomously, makes a choice that leads to widespread blackouts, economic collapse, or unintended conflict, our traditional frameworks of responsibility, built on human intent and culpability, simply buckle. We’re asking these machines to perform functions that demand judgment, wisdom, and an understanding of consequences – attributes we usually associate with human consciousness and moral reasoning. Yet, we struggle to apply our human-centric notions of blame or praise to a silicon entity.

The Human Problem with Non-Human Agency

Our legal and ethical systems are fundamentally designed for humans. They hinge on concepts like intent, negligence, foresight, and the ability to understand right from wrong. We punish, or compensate, based on these very human attributes. But an AI doesn’t “intend” to discriminate, nor does it “feel” remorse for a mistake. Its “decisions” are the output of complex algorithms processing data, optimized for certain outcomes.

This creates a profound philosophical challenge. If an AI makes a truly autonomous decision – one that wasn’t explicitly programmed, but emerged from its learning process – can we still hold a human accountable? And if we can’t, does that mean we’re accepting a future where critical choices are made without a clear locus of human accountability? That feels, frankly, a bit unsettling. It’s like sending our smart, digital children out into the world and hoping they don’t get into too much trouble, with no one to call if they do.

Closing the Gap: A Long Road Ahead

So, what do we do? Simply saying “let’s not build powerful AI” is about as effective as telling the tide not to come in. The march of progress, for better or worse, is usually a one-way street.

Here are a few avenues we might explore, none of them easy:

1. **Redefining “Control”:** We need to move beyond thinking of control as direct, step-by-step programming. Control in the age of autonomous AI might mean designing robust ethical constraints, building in “off switches,” or ensuring human oversight remains meaningful, even if not interventionist in every decision.

2. **Layers of Liability:** Perhaps responsibility needs to be distributed. The developer for design flaws, the deployer for insufficient testing or oversight, the owner for operating it in inappropriate contexts. Think of it like a complex insurance scheme, but for culpability.

3. **”AI Personhood” (with extreme caution):** This is a contentious idea, but some suggest that perhaps advanced AGIs might one day require some form of legal status to be held accountable. However, bestowing “rights” and “responsibilities” on non-conscious entities opens a Pandora’s Box of philosophical and practical dilemmas. Let’s maybe keep that one on the back burner, just in case.

4. **Explainable AI (XAI) and Auditing:** While XAI doesn’t *assign* responsibility, it’s a crucial first step. Understanding *why* an AI made a decision allows us to learn, adapt, and potentially identify where a human input, or lack thereof, might have contributed to the outcome. It’s like forensic science for algorithms.

5. **Ethical Design from the Ground Up:** This is probably our most potent tool. We must embed ethical principles, safety protocols, and accountability mechanisms into AI systems from their conception. This means prioritizing robustness, transparency, and fairness alongside efficiency and performance.

The responsibility gap isn’t just a legal or technical challenge; it’s a profound human one. It forces us to reconsider what it means to be responsible, what it means to be a decision-maker, and how we want to live in a world increasingly shaped by entities that are intelligent but not necessarily moral in the human sense. Navigating this gap requires not just clever engineers, but wise philosophers, thoughtful policymakers, and an engaged public. Because ultimately, the future with AI isn’t just about what machines can do; it’s about what *we* decide to do with them, and how we choose to hold ourselves accountable for the world we are collectively building. It’s a bit like giving a super-smart child the keys to the car; we better make sure we’ve taught them not just *how* to drive, but *where* to drive, and who to call if there’s a fender bender. Preferably before they leave the driveway.

Leave a Reply